This selection of reviews I was able to find on the internet reader's may find helpful. There are many more. If you are aware of a substantive review, send me the URL and I will post a copy of it here.

Promethea Tarot Related Reviews

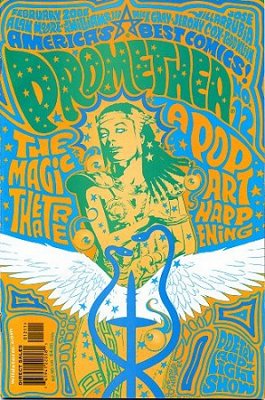

Promethea Comic: Number 12 - Tarot Issue

Review by Diane Wilkes

When I was a little girl, my grandfather would bring me comic books when I was sick. He'd throw in the occasional romance, but mostly he brought me Archies and The Rawhide Kid. Since then, I was remotely aware of the renaissance of the genre, but the only comics I purchased and read in recent years were authored by Andrew Vachss, my idea of a superhero. When I read about the Promethea comic book, I was only intrigued because the issue being discussed focused on tarot. And even then, I didn't go into my usual acquisitive bloodhound mode and track it down. After all, it was a comic book.

Fortunately, a friend sent Promethea No. 12 to me for Christmas. This is not your grandfather's comic book. I couldn't believe the level of complexity and scholarship to be found in this little baby...

The comic book "backstory" is this: Sophie is a present-day NYC college student--a NYC that is super-techno-oriented. Sophie is more interested in myths, particularly the myth of Promethea, a mystic warrior from 5th century Egypt. In the tarot issue, Sophie takes on Promethea-like qualities as she flies through the air with Mack and Mike, the two snakes on the caduceus, who explain the mysteries of the Major Arcana to her in flippant rhyme. While the tone is decidedly cheeky, the text is filled with substance, not to mention arcane references way beyond my level of magick. To show just one example of Moore's cleverness: Rachel Pollack told me that Mac stands for Macrocosmos, and Mike, Microcosmos.

There are three levels going on--the first is Sophie's trip through the Major Arcana. On the bottom of each page, there is an ongoing story regarding Aleister Crowley, and each page has Scrabble™-like tiles spelling out an anagram of Promethea that apply to the tarot card being explored. One of the many extremely clever details is the Hebrew letter equivalent at the bottom of the tile (as opposed to the traditional point value).

Some of these anagrams are, naturally, a bit forced. But I love "Pa Theorem" for the Magician, "Mater Hope" for the High Priestess, "O Reap Them" for Death, and "Me Atop Her" (!) for the Lovers. Speaking of The Lovers, you can see from the linked image that the Adam and Eve myth for this card, so recently discussed on Tarot-l, is in full force.

In fact, the trip from the Fool (something from nothingness) to the World (rebirth after the end of the world, which will come in 2017, according to this issue) parallels the birth of mankind to the present. Temperance (Art) is the Renaissance; The Moon card refers to the Holocaust (there is even the gate to Auschwitz, with the words "Arbeit Macht Frei" in front of clouds of smoke the color of blood).

There are so many levels to this comic book that I can't begin to address each one. But I was so impressed with the intelligence of author Alan Moore and the art of the many "co-creators" that I bought every back issue (Numbers one through six can be purchased in a beautiful bound volume with a blue ribbon bookmark--would my grandfather be surprised!). I highly recommend this comic book to every tarot enthusiast. And, at $2.95, this tarot publication is the best bargain I've seen in years.

While I haven't begun to read my Prometheas (darn update!), Rachel Pollack told me that there are other issues that feature the tarot. It seems that Issue Seven contains a partial photo version of the Frieda Harris Universe card.

Promethea Number 12

Alan Moore

www.wildstorm.com

Art and text © 2000 Alan Moore; J.H. Williams; Mick Gray; Jose

Villarrubia; Jeromy Cox; Todd Klein

Review and page © 2001

Diane Wilkes

Promethea: Book One

Writer: Alan Moore

Artists: J.H. Williams, III, Mick Gray and Charles Vess

Painted cover by J.H. Williams, III and José Villarubia review by Andrew Gilstrap From

O! Promethea!

There's a reason the Romantic poets were so fond of invoking the muses before they embarked on Odes to various pastoral objects. It wasn't just a nod to Classical forefathers like Homer, but also to the fact that creation, by its very nature, is a mysterious, intangible, and highly unreliable thing. When the words are flowing, or the music is pouring out with little help from the conscious mind, it's tempting to think there must be some other force at play besides the hard-to-reach recesses of the mind. Enter entities like the Muses, who are such an accepted part of our creative mythos that they've made the leap from Hamilton's Mythology to mainstream culture (most recently in films like Albert Brooks' The Muse and Kevin Smith's Dogma). Even comics have brushed up against the topic, with an early issue of Neil Gaiman's The Sandman dealing with a writer who profited creatively from holding a muse captive in his attic. Alan Moore, however, takes the muse one step beyond her traditional role, and into the realm of the superheroine, with Promethea.

Gaiman's tales in The Sandman revolved around the impact that stories have on us. He kept things archetypal, and even when mundane characters were involved, they were part of a larger scheme and often found themselves pegged in archetypal roles themselves. Moore, however, keeps Promethea very much in the realm of the personal.

Ostensibly the story of Sophie Bangs, a New York college student, Promethea actually plants its roots much farther back, in Alexandria 411 B.C. A child cries out to her murdered father's gods, summoning Thoth-Hermes, a curious combination of Greek and Egyptian deities, who takes her into The Immateria with the promise that she "would live eternally, as stories do ... sometimes, if a story is special, it can quite take people over." Flash forward to New York in 1999, which resembles a less rain-soaked version of the Blade Runner set, with flying vehicles, neon advertisements for miles, and a group of Science Heroes who help keep the peace.

Sophie is researching Promethea for her term paper, having noticed that the name repeatedly pops up in literature, comic strips, and battlefield lore. After interviewing Barbara Shelley, the widow of the last man to write about Promethea, Sophie is attacked, only to be rescued by Shelley in her guise as Promethea. After being severely wounded and forced to retreat, Shelley explains Promethea's true nature to Sophie — that Promethea is a living story who can be brought into reality by a strong, focused imagination. The creator can become Promethea, or project it onto someone else, as Shelley's husband did. Still under attack, Shelley tells Sophie to write about Promethea. Sophie becomes Promethea — possibly the strongest yet — and makes short work of her attacker.

Promethea, as Moore's use of a hybrid Egyptian/Greek deity would indicate, bears resemblance to earlier comic heroines Isis and Wonder Woman, garbed in a white tunic and golden armor, and wielding a caduceus that bristles with blue, heavenly electricity. Personified in Sophie, she is initially raw power, with the intellect of Promethea and Sophie's wide-eyed naivety battling for control. Both consciousnesses coexist simultaneously, and one of the book's greatest themes is Sophie/Promethea coming to terms with this awesome amount of power. Much like the writer or musician who has the innate talent, but who must hone and refine that talent into actual learned skill, Sophie must learn to handle her challenges as Promethea with more than brute force. And those challenges come immediately.

A secretive mystic group known as The Temple puts a hit out on Promethea, hiring fallen angels who, in black suits and ties, resemble extras from a Quentin Tarantino film. After she virtually obliterates the first two, the entire fallen host is called out to take her down. After the battle, Sophie realizes that she must undergo more formal training than mere battle-hardening, and ventures into The Immateria. A psychedelic version of Little Nemo's Slumberland, The Immateria is a realm of imagination where pure archetypes like The Wolf in Little Red Riding Hood are at full power, and isolated pockets are carved out by writers' imaginations. It is also where the previous Prometheas exist in presumable retirement, doing little more than eating, drinking, bickering, and watching the current Promethea. Each of them, in turn, tutors Sophie in a different aspect of Promethea.

As a superheroine comic book, Promethea brandishes the requisite amounts of action, but Moore also lays a solid intellectual foundation that's only heightened as the series progresses past this first collection. Sophie delves deeper and deeper into the mysticism and magic that informs Promethea, studying Kabbalism, sex magick, and Tarot symbolism, becoming stronger and more confident in the process. It's pretty heady stuff at times, with Moore taking what he needs to construct his map of the intellect, and never delving too deeply into any one mystical pocket. It's not hard, though, to see that Sophie's struggle and development are like those of any creative person. Brute creative force can get you through your initial challenges, but as you strive for more ambitious projects and the competition is increasingly more talented, your studies must come to the fore. Sophie's development is highly accelerated — the benefits of a godlike power murmuring advice in your skull, I guess, and fallen angels on your heels — and by the most recent issue, she's on a quest through the afterlife. But in watching her solve as many dilemmas with intellect and logic as she does with her caduceus a-blazin', satisfaction can be the only result for anyone's who's ever tried to put together the pieces of a creative puzzle.

Promethea — Recommended

Promethea is perhaps the most pure expression of some of the key themes of writer Alan Moore’s work.

It’s the story of Sophie, a college student in the near future. She’s been studying the various mythical appearances of Promethea, a warrior woman who’s been the subject of epic poems and pulp illustrations and comic books. When an evil spirit attacks, Sophie uses the power of story and imagination to become the latest version of Promethea, guided by previous incarnations. In other words, the stories we immerse ourselves in affect who we are, and we can become whatever we imagine ourselves to be.

The city is a paean to science, with floating taxis and neon screens and flying police saucers and and immediate media narration and its own team of protective “science heroes”, the Five Swell Guys in suits. In addition to a relatively straightforward “use magic to fight the bad demons” plot, there are tons of throwaway ideas and background information here that are wonderful creations in their own right. Take, for example, Weeping Gorilla, a crying ape who thinks one sad cliched catchphrase at a time. At first, he seems like a throwaway running gag, but later, he becomes more as others invest emotional power in him. The same goes for the foul-mouthed version of Red Riding Hood who pops up as a guide.

Then there’s the Immateria. (Aren’t these names perfectly chosen? Impressive-sounding and evocative.) That’s the land of fiction and myth where the previous heroines still live. Various versions of Promethea were invented as they were needed by their authors, whether a failed poet in the 1700s falling in love with a dream version of his maid or a female illustrator of pulp magazines in the 1920s fed up with the lewd sexism of her male editors or an artist who imagined himself being the ideal woman. I particularly like the little-girl version who annoys the others; she speaks like the Little Nemo character from the classic early strip.

The gorgeous art by J.H. Williams III and Mick Gray perfectly stands up to the demands of the text, bursting with images and fully packed, like the story itself. Creative vistas bring form to Moore’s ideas and principles. In addition to showing all the details and characters and events, there are elaborate page designs that work in mystical elements, adding to the feel of a book that reveals more to you the more you invest in it. And their Promethea is classically exotic, full of power and magic.

This first volume establishes the premise and shows Sophie the meaning of compassion, insightful reason, and righteous violence. Book two continues Sophie’s trip through the character’s history and the land of imagination. William Woolcott, a gay writer/artist who was the host of Promethea during her most playful time, as a children’s comic, teaches Sophie about the wonders of physicality in a sequence illustrated with treated photographs.

Like the end of the Buffy the Vampire Slayer TV series, Moore sets up traditional superhero structures — oh, no, a band of demons are attacking a hospital! how will Sophie transform into Promethea to save the day? — and then undercuts the reader’s expectations. Instead of a solo hero evoked through some grandiose gesture, Sophie uses poetry to open the door and then brings through multiple versions of female power. Or she ends a decades-long vendetta through amusing the next generation instead of battling them. The ability to improvise outside of existing patterns is Sophie’s strength.

Book two continues the physical theme with Sophie looking for more magical instruction, which she winds up obtaining by having sex (as her alter ego) with a troll-like old man fortuneteller. In addition to representing many readers’ fantasies, this sequence marks the transition from story to instruction manual; from this point forward, the book becomes Moore’s lecture about his ideas of how magic works, beginning with a walk through the Tarot as representative of human history. The art, in conjunction, becomes symbolic, with allusions and anagrams, references and experimentation galore.

In books three and four, Sophie as Promethea goes venturing through the higher planes and the planets, representing the Kabbalah Tree of Life, in search of a departed former heroine, who is herself seeking her former love.

As book five opens, it’s three years later, and Sophie’s in hiding from the FBI, who have enlisted Tom Strong to find her. The style returns to more traditional comic book art temporarily, before Promethea’s final transformation brings about the end of the world in a uniquely Moore-ish way. The last issue is barely a comic any more, with line drawings and captions scattered over pastel swirls of color which combine to make two large poster images.

Although superficially resembling Alan Moore’s take on Wonder Woman, by its end, Promethea symbolizes unlimited potential in an eye-opening series celebrating imagination and magic.

A Review of PROMETHEA By Rob Vollmar

This review/discussion of the complete PROMETHEA ran in the

November 2005 issue of the Comics Journal. As you can see, the

titles I came up with for this one were soooooo good that I

couldn't choose between them and delivered it with two, ala

BULLWINKLE. I hope you enjoy!!

From

How Do you Solve a Problem Like Promethea?

or

YHVH YMMV

By Rob Vollmar

Promethea #1-32

Alan Moore, J.H. Williams, Mick Gray, various

Available in five collected volumes from DC/Wildstorm

In 1999, Alan Moore, along with artist, J. H. Williams III and

an A-list production team, debuted an ambitious new series,

PROMETHEA. The title was nestled among five other new Moore

series, LEAGUE OF EXTRAORDINARY GENTLEMEN, TOM STRONG, TOP TEN,

and TOMORROW STORIES, the latter three of which plus PROMETHEA

made up the America’s Best Comics imprint. For his two ongoing

serials, PROMETHEA and TOM STRONG, Moore crafted title

characters that represented the essence of something broad,

presumably to appeal to the widest group of readers in reaction

to the perceived insularity of the Direct Market audience.

Considered in a context with the other ABC titles, it is easy to

understand why most of PROMETHEA’s audience thought that they

had bought a comic book determined to brighten the timbre of

superhero comics in general through an infusion of older, less

embittered blood, as reconstituted by one of its finest writers.

In this respect, Promethea and her creators make good on their

promise to show us some real magic by pulling none other than

the old bait-and-switch and delivering something quite different

from the rest of the ABC line.

Tom Strong is...well, strong in every sense of the word. He is a

blend of familiar figures like Superman, Captain America,

Tarzan, and John Carter and, as such, is presented as the zenith

of masculine individualism. Promethea, in contrast, is the

embodiment of feminine Imagination. In the opening story, “The

Radiant, Heavenly City,” there are recognizable strains of the

superhero tradition that can be picked out. Though Billy Batson

had to utter but one to transform into his more formidable self,

the transformation of Sophie Bangs, young college girl, into

Promethea via the power of the word is an unmistakable echo of

characters like Captain Marvel or Johnny Thunderbolt. Her role

as the world’s protector against the dark, supernatural powers

that threaten to engulf it as well as her facility with magic

pay homage to Marvel’s DR STRANGE and, more broadly, to a holy

host of forgotten magicians who moonlighted as superheroes like

Zatara, Drr. Fate or Ibis the Invincible.

THE NOVICE (Promethea 1-12)

The first eight issues make up the opening arc and function as a

protracted origin story for the title character. This is but one

of a gaggle of signifiers to suggest that PROMETHEA is intended

to be read as a superhero (or science hero as Moore lovingly

dubs his ABC version) comic book. The current Promethea takes

over the mantle from the wife of a deceased comics writer who

had herself taken it up from a gay comics artist that was killed

when her lover discovered that she was actually a he. Through

this device, a continuity is created for the character that

stretches back to the 5th century, producing, as if by magic, a

trove of narrative riches to mine that would be difficult to

equal in one hundred uninterrupted years of real-time print. In

addition, one of the major subplots introduces the local science

hero team, the Five Swell Guys, and keeps the genre allusions

close to the center of the story by having their latest battle

with the maniacal Painted Doll intersect with the climax of the

first arc.

The ruse that Promethea is a science/superhero is left

unchallenged for nearly two issues. The dystopian present,

framed cinematically and dominated by shadows except when

illuminated by the brilliance of her presence in it, gives way

to the fluid and colorful layouts that take place inside of

Promethea’s native plane, the Immateria. Her first battles are

won on instinct alone but, in order to face the onslaught that

is coming, she is instructed by a variety of former Prometheas

on the meaning and use of her magical weapons. Trading fours

with the superhero mess that is brewing in the material world,

these more expository sections explore the newly created

continuity by introducing earlier versions of the character as

well as laying the foundation and framework for the use of magic

in the story.

The role that Williams and the production team play in this

frequent transformation can not be overstated. Though certain

structural elements, like layout strategies or color schemes,

can be dictated in the scripting, nearly every facet of the

visual presentation is conscripted to the cause. As the story

progresses, this expression of comics art as shifting state of

consciousness becomes more pronounced and, one might assume,

more challenging to envision and maintain.

Despite this struggle between conflicting worldviews that rages

on for five issues before deciding to duke it out in issue

eight, PROMETHEA’s more orthodox qualities keep the pacing brisk

and the action frequent enough. Only once or twice in this first

arc do characters cut loose with a verbal barrage like:

Promethea makes people more aware of this vast immaterial realm.

Maybe tempts them to explore it. Imagine if too many people

followed where she led? It would be like a great Devonian leap,

from sea to land. Humanity slithering up the beach, from one

element to another. From matter...to mind. We have many names

for this event. We call it “The Rapture.” We call it “The

Opening of the 32nd Path.” We call it the Awakening, or the

Apocalypse. But “end of the world” will do. (Promethea, 5:13)

Regardless of how one reacts to the content of the expository

material, it undoubtedly slows down the process of interpreting

the page. Offered in limited doses and interspersed among

intense action scenes though, it is an intrusion that is easily

tolerated without threatening the identity of the series as a

whole.

After a brief denouement in issue nine, PROMETHEA begins its

shift towards something quite different. Issue ten’s, “Sex,

Stars, and Magic” is the warning shot across the bow, dedicating

twenty-two of its twenty-four pages to a comics adaptation of a

tantric sex act between Promethea and magician Jack Faust. The

contour of the panel transitions takes on a suggestive role,

shifting in two-page blocks that tightly control the path that

the reader follows across the spread. For the first time since

the series began, PROMETHEA abandons the real-world tethers of

cinematic storytelling, relying on inventive layout strategies

and lots of evocative narrative to recreate a variety of altered

states of consciousness on the page. Though the mechanics of the

manner in which the story is presented are fascinating in and of

themselves, the payoff for the receptive reader can be deeply

emotional but only if they allow themselves to be taken in by

Moore’s magic spell.

Promethea #12 is another text-heavy, “learning-the-ropes-about

magic” story, this time featuring commentary on the Tarot. While

“Sex, Stars, and Magic” is the most controversial segment of the

first twelve issues, “The Magic Theatre” is without a doubt, the

most complex. Each page, excepting the first and the last, is

dominated by one card of the Tarot, progressing sequentially

through the Major Arcana. There are three streams of internal

narrative that move down each page, two that alternate after two

rhyming couplets and Promethea’s that reacts alongside them. The

bottom third of each page is intersected by a

horizontally-sequential strip, a joke in 22 parts on the nature

of magic as told by Aleister Crowley as he ages progressively

from zygote to memory. Lastly, Scrabble tiles that spell out the

word PROMETHEA on page one are re-arranged for each page to

reveal an unexpected correspondence to the card featured, as

well as a second horizontal element for the page.

The forward momentum taken from these two, less substantial

narratives is overpowered by the downward crush of the bulk of

the text running down the page. The result is a set of static

pages that encourage the reader to separate the narrative and

visual streams of information and, in doing so, again, dwell

upon the page longer than usual in their interpretation. The

down side to this approach is that the measure of its success is

obviously tied to the reader’s interest (or lack of it) in the

Tarot or, at the very least, the interpretation of it offered

here in lavish detail. The tropes of the superhero genre are

abandoned so absolutely that one begins to suspect that either

the presumed function of the work, superheroes play-acting at

magic, has shifted or was deceptively constructed to allow for a

second aesthetic, magic play-acting as superheroes, to gradually

emerge from the first.

THE INITIATE (13-23)

Underscoring this departure, issues fourteen through

twenty-three are given over almost wholly to this seemingly new

agenda of using comics to approximate the altered states of

consciousness associated with Kabbalist ritual practice. Moore,

a practicing magician since the early 1990s, first nurtured the

impulse to externalize his internal experiences with the

Kabbalah through his spoken word performance THE MOON & SERPENT

GRAND EGYPTIAN THEATRE OF MARVELS (CD, Cleopatra Records, 1996).

Where that piece is limited by duration though, PROMETHEA

provides its creators with a canvas restricted in length only by

the pressures of the marketplace, allowing for a sustained

experiment in using comics to effectively transmit the core

myths and values of a particular faith. Each segment in this

ten-issue stretch is designed to reflect one of the ten

landmarks or sephira as Promethea passes through them on her

journey up the Tree of Life. These various altered states are

given a life beyond the chatty dialogue, translated visually

through a variety of means that subconsciously reinforce many of

the correspondences shared by a given portion of the Tree

without dumping it all through the narrative.

But, like the Abyss that Promethea must cross in order to reach

the Supernal Triad, this ten issue stretch represents something

of a chasm between those readers who are willing to place

themselves subject to Moore and Williams’ executive narrative

authority and those who are not. If the critical hinge was

affixed upon whether or not PROMETHEA makes full and effective

use of the natural strengths of storytelling with comics, there

are few that could dispute the high level of craft consistently

on display. What may be questioned though is the degree of

tolerance required by the uninterested to slog through

expository dialogue about the nature of existence, however

immaculately rendered. Given the polarizing nature of the

content and the primacy that its delivery is given over all

other narrative concerns, mere apathy may, in some cases, trump

a detached appreciation of the visual and narrative techniques

employed resulting in boredom or worse.

THE MAGICIAN (24-32)

The two issues after Promethea’s return can be read together as

a bridge between the magickal journey of the second section and

the literal apocalypse that is to come. Despite the impassioned

allegory to contemporary political problems Moore is able to

piece together from strings left untied during Promethea’s

magical, mystery tour, the function of this segue is to set the

series up for a shift into the future. As issue twenty-six

opens, we find our story has moved ahead three years as the

authorities have hunted in vain to uncover Promethea hiding in

her more mundane form under an assumed identity.

It is impossible to discuss the ending of Promethea without once

again referencing the other titles in the ABC line as the end of

the former also spelled the end of the latter. As Sophie is

finally exposed as the Promethea destined to bring about the end

of the world, the majority of Moore’s other ABC characters (with

the exception of the cast of TOP TEN) show up to stop her. Moore

had, by this point, lost his taste for the work-for-hire

arrangement under DC/Wildstorm that ABC represented and

terminated his involvement with all the ongoing serials with the

exception of PROMETHEA. This crisis on Earth ABC would be for

all the marbles that Moore had left in his pouch on someone

else’s dime.

For all the bacchanal bluster that the creative team is able to

deliver as these end-times are documented, the crisis proves to

be more revelation than conflict. While the obstacles to this

final display of Promethea’s unique purpose seem a bit contrived

given the ease with they are overcome, Moore, Williams and

company come together one last time to deliver a truly

spoon-bending story that flows back and forth between the two

struggling narratives. Finally, in issue thirty, the superhero

element of the book, represented in its purest form by a

“showdown” between Promethea and uber-science-villain, the

Painted Doll, is quietly subsumed for the last time in the

magical content. This conflict at rest, PROMETHEA is poised to

perform her final trick.

Issue thirty-one is the last in the ongoing serial narrative

though the series would conclude with the one that followed.

After a few pages of set-up, Moore breaks the fourth wall by

having Promethea guide the reader directly through the final

throes of the ABC-pocalypse. Through this narrative device only

one step removed from direct address, Moore makes his final

argument for the validity of using PROMETHEA as a vehicle for

religious expression:

See, I’m imagination. I’m real and I’m the best friend you ever

had. Who do you think got you all this cool stuff? The clothes

you are wearing. The room. The house, the city that you’re in.

Everything in it started out in the human imagination. Your

lives, your personalities, your whole world. All invented...Yes,

Promethea’s fiction. Nobody ever claimed otherwise. I never

lied. I'm at least an honest fiction. A true fiction. A fiction

that can enter your dreams, possess her creators, talk through

them to you. I’m an idea but I’m a real idea. (Promethea 31:6-7)

This technique, similarly exploited by Moore in the final

chapter of his novel VOICE OF THE FIRE, is effective at keeping

the weary reader’s attention for final barrage of spiritually

motivating exposition, superimposed over elaborately rendered

but static full-page images. The last few pages are then given

over to a brief look at the ABC Universe that could exist beyond

Moore’s active contribution to it which, given the market

mechanics in play in the Direct Market, we will undoubtedly see

more of, for ill or for well.

The ending, for the most part, lives up to its spiritual duties

as an approachable and well-considered restatement of beliefs

held in common by a goodly number of otherwise pagan faiths for

the now-indoctrinated devotees that remain. As the resolution to

a Universe shattering crisis, it comes across not surprisingly

as something of a deus ex machina ending that might leave a more

skeptical reader wondering if Moore really needed four whole

issues to build up to what was, after all, a foregone

conclusion.

Whereas issue 31 is the end of the world as we knew it, issue 32

is the actual final issue of the PROMETHEA series. Here, Moore

and Williams create one final, intricate piece of comics which

serves both as a summation of the ideas explored in the story

and as a last, best chance to pull off an elaborate formalist

experiment. Each page is essentially self-contained and, as

such, can be read in almost any order without losing the

narrative thread. If the pages are removed and separated, they

can also be re-arranged in a fashion that reveals a larger

images of the series’ title character that are otherwise

invisible when taken one page at a time.

This final meeting of PROMETHEA’s creative team can be

critically read as a metonymy for the series as a whole. From a

technical perspective, it is unassailably the work of gifted

comics creators who have command of a wide-range of visual

storytelling techniques determined to steam ahead to less

explored ground through their collaborative work. That shared

palette is given over however to content that denies the reader

an objective position from which to approach the story. In order

to follow Promethea on her journey from novice to magician, her

creators demand a suspension of disbelief from the reader that

can’t end when the last page of the story is rendered and

consumed. Like the super-fancy final installment, PROMETHEA, as

a series, will prove difficult if not impossible to appreciate

for the reader lacking the faith to pull apart their

expectations for the narrative and reorganize them according to

the creators’ wishes, only to reveal something otherwise unseen.

For those who are, Promethea’s story becomes an inspired and

deeply moving testament to the potential of human imagination to

rise above the death and squalor of everyday life. Her creators

elect to use that same imagination to envision a new kind of

superhero, namely one whose exploits and experiences could

potentially transform the interior of its reader in a way that

is both meaningful and radical. In retrospect, it seems only

fitting that Moore and Williams are willing to wager the success

of the piece on the reader’s willingness to engage PROMETHEA as

something more than just a superhero comic book. Anything less

would have been a guarantee that no one would.

contents this page

PROMETHEA: Main Page Teleconference Info

PROMETHEA: Notes and Annotations by Eroom Nala

Paul's Early Review of the Series

Synopsis of Promethea Chapters

Promethea Comic: Number 12 - Tarot Issue

Review by Diane Wilkes

Promethea: Book One

Writer: Alan Moore

Artists: J.H. Williams, III, Mick Gray and Charles Vess

Painted cover by J.H. Williams, III and José Villarubia

review by Andrew

Gilstrap

Promethea — Recommended

A Review of PROMETHEA By Rob Vollmar